TIGInterview: Alex May

By: Derek Yu

On: April 9th, 2009

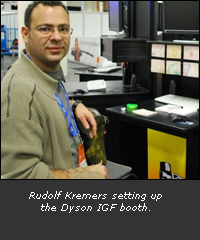

Leigh Ashton, AKA Gravious, recently interviewed his good friend Alex May about Dyson, IGF 2009, and what it’s like to be a part of indiedom.

Leigh: So Alex, for those who don’t know who you are, could you please introduce yourself and tell us a bit about your games?

Alex: I’m Alex May. I am fascinated by interactive systems. I currently work in the games industry full time and write the real stuff in my spare time. That’s actually a bit unfair to my current employers. The project I’m on at work is rather fresh, and our own thing by and large. I wrote Cottage of Doom, which won the TIGSource B-Games competition and wrote Dyson along with Rudolf Kremers.

Leigh: You’ve just come back from the Independent Games Festival, how was that?

Alex: It was one of the best weeks of my life. I had never been to America before, never been to a conference before, never been nominated for an award before. It was amazing. Just meeting so many of my fellow indies was more than worth anything I’ve put into Dyson so far. Dyson may not have won the awards for which it was nominated but we really don’t mind about that. The games that did win absolutely deserved to and for us, the nomination itself has been an astronomical boost. Really, it’s been life-changing just to be nominated.

Leigh: Your most recent game Dyson was a finalist for the Seumas McNally grand prize, it started off as an entry in one of the frequently held competitions here on TIGSource, were you surprised at the reaction its received?

Alex: Yes, but also no, in a way. I think I also speak for Rudolf when I say that the response we’ve received has changed the way we think about our work. Personally, I was surprised that so many people could enjoy our game, which I considered to be flawed and incomplete in every aspect. However, we ourselves tried hard to create something a little surprising, so it is good to see that people are finding that refreshing.

Leigh: You’re releasing Dyson commercially through Steam and Direct2Drive in July, How has that experience been so far?

Alex: Super. Both companies have been extremely supportive and responsive. It’s been a breeze, both in terms of being easy to go through the process of signing a deal, and in terms of dealing with people over financial matters.

Leigh: Most commercial games are the product of market feasibility studies and intense demographic targeting, yet indie developers frequently just make the games they want to play. What are your motivating factors in game design or implementation?

Alex: If it’s not fun, we remove it. Eventually. For me, all elements of the design should support each other. Finding ways of doing that can be like piecing together a huge jigsaw puzzle, which might even have bits missing, but eventually you get something like a full picture. For instance, it is important that Dyson trees cost a certain number of seedlings, for the design. But the trees only grow from one spot, right? So for the implementation, I had those other seedlings land on the surface of the asteroid and become grass. For ages we just had them explode in the air and the tree would magically grow out of the asteroid, but now it all makes a bit more sense.

Leigh: Have these ideals moulded Dyson, or since “going pro” have you adopted a more business oriented design approach?

Alex: I think I got a bit scared by going commercial and I wanted to make sure people would get value for money. But in doing that I think I miscalculated what people would see as value, or forgot what made our game valuable, and I helped make plans with Rudolf that might have made the game worse. I talked to Jonathan Mak at GDC and he helped me realise this. We’ve looked at the plans since and applied what we learned from players at the IGF so that we can stay close to the indie dream.

Leigh: What do you think the pros and cons of this approach are?

Alex: Doing it indie? OK here goes: In the Pros corner, you’ve got the love. That’s the main thing. And if you’re not free then you can’t realise that love, make it real. Tale of Tales did a presentation at the Indie Game Maker Rant at IGS where I think they told us how indie they are… or something. The point was, nothing influences them except themselves. That’s what I took away from it anyway. I’m usually quite pessimistic, but I strongly believe that if you stick to your principles then it all works out in the end, regardless of the Cons.

Leigh: A lot of people commented that some of the entrants to the IGF were from mainstream published studios and shouldn’t have been allowed. This raises the question of what it is to be “Indie”. Do you think “indie” is a market, like “Casual” games, and therefore a valid target, or is it simply an ideological stand to the publishers lack of creative risk taking?

Alex: ‘Indie’ isn’t a market, it’s a word, and it’s short for ‘independent’. In this case, independent games. So I don’t think it’s a market, no. I don’t think casual games is a market either. I think there is a clear market for simple, family-friendly downloadable games, because it has been captured and hungrily developed. A market is a place where people go to buy things. All those people know roughly what they will get when they shop at certain places or with certain companies, organisations, brands or people. People who visit Big Fish are Big Fish’s market, and the market for anyone who sells through Big Fish. People who use Steam are Valve’s market, and the market for anyone who sells through Steam. But the so-called casual portals have fallen into the same trap as the mainstream publishers – they’re on to some money and that’s repeatable, and it’s something they can statistically rely on, so they don’t change what they’re doing. This has created the myth of the ‘casual’ game. When people do the same thing a lot it becomes typical. Anyway, these games aren’t casual; some people spend hours on them at a time. What they are is good games that appeal to certain people. A truly casual game would spit you out after half an hour and tell you to come back the next day. Dyson has been called a casual game because it is quite simple, but you can spend hours doing the same clicking and dragging. It’s not casual, it’s just quite easy to play and it’s compelling.

Now if you look around on indie game sites, you’ll see people (developers and consumers alike) complaining that (for example) “all indie games are crap” or “all indie games are unrefined” or “all indie games are arty nonsense”. All this proves, apart from that people are stupid (and we knew that already), is that indie games are diverse, which makes sense because the only creative barriers around an independent game are that there are none. They don’t fit into any one market by definition. They’re just games, and some are good and some are bad and some of them will appeal to you and some won’t.

All that said, there will be a small minority who are interested and any indie game just because it is indie – idealistic consumers and pursuers of creative freedom or pretentious art hipsters? It’s your choice. It could be considered a market by a bad businessman. I don’t think it’s particularly significant in business terms, but at any rate it is interesting to see the positive and negative stigmas that are associated with the word ‘indie’ by the public now.

I try not to let any of this bother me though. Just focus on what you love. That’s a bit hypocritical, because sometimes I say bad things about games or people, but one ought to focus on what one likes and ignore the rest. Do as I say, not as I do! You there! Take your shirt off at the award ceremony!

Leigh: could it simply be that the “bedroom coder” has come full-circle?

Alex: They never went away, it’s just that they can more readily make money again now. Great!

Leigh: The irony is, most of the kids making games now probably never used the computers that kickstarted our industry, a 16 year old for instance, wouldn’t have even been born when Commodore imploded, taking the Amiga with it..

Alex: I miss it too man, but you gotta let it go. It’s gone. We’ll always carry it with us. We’ll always have Alien Breed, and Lemmings, and Exile. We’ll always have Workbench, and Deluxe Paint II, and AMOS. Red Sector, Fairlight, and Parallax. 4-Mat, Drax, Tim Wright. Let’s celebrate it, not mourn it!

Leigh: Old games from defunct platforms aren’t as easily accessible to people as say, old books, or even film, do you think this is depriving young developers or even just gamers, of our rich gaming heritage? Is that even a problem, really?

Alex: We write our own history in this respect. There were probably loads of great books written well before their time, as it were, that have not been preserved in enough numbers to be significantly remembered historically. Same with music. It is important to save them. They contain rich history. But they do get saved, and there are people out there saving games, probably to a more efficient extent than any other medium ever. I have seen entire collections of every known game ever released on a platform made available. I checked, and the rarest games I knew were on there and reportedly worked. But really, I know most of what I know of old media from my parents. My dad just bought a DVD of old 1920s jazz MP3s. He spent years collecting tapes and records from that period, only to be able to buy a massive great chunk of it on eBay for four quid. He says it’s the best four quid he’s ever spent.

So teach your kids about old games, why people made them, what trends and forces shaped their creation. It’s important.

Also, I should put a save game system in Dyson. Thanks for the reminder.

Leigh: Do you see a distinction between amateur game makers and indie game makers?

Alex: This comes from that Andrew Doull article. It was stupid then and it’s still stupid because it’s a false dichotomy. Amateur means non-professional. Independent means free. These are not the same. Imagine instead of a single dimension, where at one end of the line you have amateurs and free games, and at the other you have indies and commercial games, you have a two-dimensional space, where on one axis you have amateur and professional, and on the other you have freedom and constraint. Then you will see the real terrain.

Leigh: Where do you see Indie games going from here?

Alex: As a whole it will become, and in many cases has become, a viable medium for people to create any kind of interactive entertainment and live off that to some extent. It’s quite diverse now, with self-published indies operating out of their own sites, and distribution channels available on PC, Mac, XBox 360, PS3, Wii, and mobile platforms. The tools are ripe for picking too – just look around and see the richness: there’s Unity, Game Maker, Multimedia Fusion, BlitzMax, Torque, XNA, pygame, and a ton of other engines and frameworks. There’s never been a better time. If you ever thought about making a game, you can pick up a tool and get to work right now. You can do it.

Leigh: Finally, any tidbits on what you guys are up to after Dyson is released?

Alex: We’re going to work together on another project. I can’t say what that is yet, as we’ve yet to come to a 100% conclusion on it, but we’re both pretty sure of what it will be by now and we’re very excited by that. I want it to be a commercial game, because I want to do this for a living, but that isn’t going to drive me. It will be something we do for the love of it, so no second-guessing the market or focus testing too early, or any of that crap. Rich gameplay and wicked styles.

Leigh: Thanks for answering my questions Alex, some very thought provoking answers! All that’s left to say now is best of luck with Dyson, and are we still cool for the level that spells out my name when you zoom out? ;-)

Alex: I’ll put it in right after that cheque clears.

-

toastie

-

Alec

-

Kinten

-

Corpus

-

http://0xdeadc0de.org Eclipse

-

Rudolf Kremers

-

Günter

-

SilverSpoon

-

Melly

-

Tanner

-

http://b-mcc.com// BMcC

-

http://www.superbrothers.ca/ superbrothers

-

PoV

-

Nava

-

Adamski

-

mirosurabu

-

Kinten

-

JoeB

-

Craig Stern

-

http://www.dyson-game.com Alex May

-

http://www.dyson-game.com Alex May

-

Aubrey

-

JoeB

-

corpus

-

JoeB

-

Kermit

-

http://www.dyson-game.com Alex May

-

http://www.dyson-game.com Alex May

-

Corpus

-

Gravious

-

JoeB

-

http://www.dyson-game.com Alex May

-

RayRayTea

-

RayRayTea